Rabbits are essentially Spanish. They evolved as Oryctolagus cuniculus on the Iberian peninsula, which was known by the Carthaginians as ‘Land of the rabbits,’ which eventually became ‘Ispania,’ and then ‘Espania.’ Rabbits remained Spanish and wild until the Romans showed up. Possibly bored of eating dormouse, the Romans rounded up the rabbits into enclosures where they were bred for food. This practice spread all over the European continent where the perfect combination of propensities for shagging and digging led to rabbits to multiply all over the place.

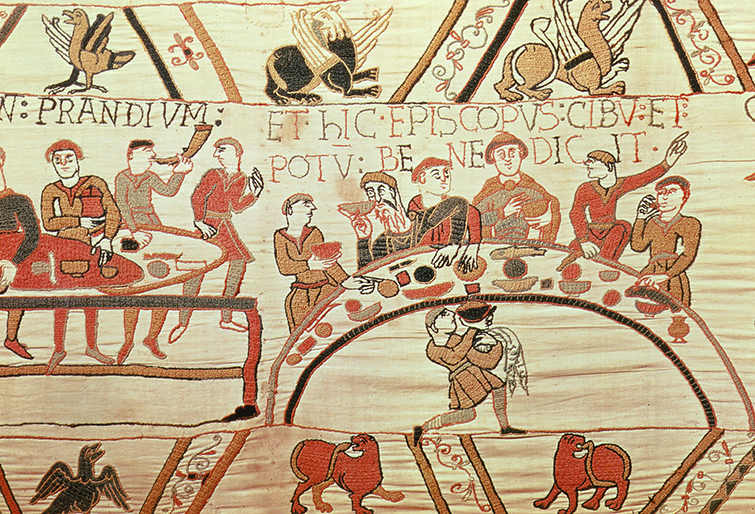

In Britain, rabbits had something of a false start. Discovery in 2005 of 2,000 year-old rabbit bones near Thetford tells us that the Romans had shipped them over from Iberia. However, other historians have long held onto the idea that it was the Normans who established rabbits in the UK. Both theories may be true whereby the Romans had a bit of a tough time establishing rabbits in Britain due to a large population of wild predators. The Normans, who turned up in 1066, were certainly very successful at raising rabbits for food and fur, and then the British countryside was overrun with the things.

By the Middle Ages, rabbits were a hugely important source of protein. One pair of rabbits can reproduce to produce 90kg of meat annually. Monks observing fasts were allowed to eat the embryos of rabbits because they were not technically considered to be ‘food.’ As a food for the poor, rabbits were very popular because they were so abundant, and relatively easy to snare (note that shooting rabbit with a 12-bore shotgun is problematic as there is a very high chance of hitting something else like a beater or your own dog).

Decline in British rabbit eating began in Victorian times when people started keeping them as pets. In 1953. Myxomatosis arrived in the UK, and was used until 1954 to control rabbit populations. Estimates suggest that 99% of the British rabbit population died in the epidemic. The idea of ‘rabbit’ was now linked to the idea of ‘disease.’ Around the same period, butchers’ shops gradually stopped the practice of hanging whole game in their windows. Rabbit was now out of sight, out of mind and out of fashion.

If you want rabbit in the UK these days, you really need to go to an independent butcher and ask what is in the freezer. The chances are that there will be rabbit.

Back in France, Spain and Italy, our continental chums continued to breed, kill, cook and eat rabbit. Tasting a lot like dense chicken, rabbit is a meat that really demands to be braised. When a cook goes looking for a French recipe for rabbit, one dish keeps popping up – lapin à la moutarde (rabbit with mustard, aka lapin à la Dijonnaise). Working out where the dish comes from though is very difficult. Both Larousse (French) and The Silver Spoon (Italian) include a version of it. Escoffier’s Le Guide Culinaire does not include it. Nowhere does anyone say where it comes from, but it does look like the kitchens of Burgundy consider it to be their own, possibly because Burgundy has Dijon as its capital, which used to be an important centre for mustard manufacture (no mustard is now made commercially in Dijon).

The Larousse version of rabbit with mustard looks awkward as it uses an oven and continual basting, which is a sure-fire route to dry meat. The Silver Spoon edition braises in wine to which mustard is added. Many chefs have published very simple recipes with just cream and mustard, but the one that struck us as a winner is that by Australian-based French chef Stephane Nguyen of the self-styled French Cooking Academy. This version uses a fricassee method where a rich velouté is made from stock enriched with rabbit trimmings and finished with cream and mustard. The recipe given here is lightly adapted from that of Nguyen. We serve this with tagliatelle, as this consistently emerges at the ‘right’ carbohydrate for the dish (Simon Hopkinson recommends steamed new potatoes). Pasta was introduced to France by Catherine de’ Medici, who married the future King Henry II of France in 1533, so French pasta is legit.

You can watch Stephane Nguyen making the dish here:

Lapin à la moutarde

Ingredients

- For the rabbit:

- 1l chicken stock

- 1l water

- 1 carrot, diced

- 1 stick of celery, diced

- 1 onion, studded with 8 cloves

- 1 bouquet garni (bay leaves, thyme and parsley stalks tied up with string)

- 2 rabbits jointed with the bone trimmings reserved

- 50g unsalted butter

- 1 onion, finely chopped

- 4 tbsp plain flour

- 60ml double cream

- 4 tbsp Dijon mustard

- 2 tsp thyme or tarragon, chopped

- For the mushrooms:

- 150g button mushrooms, cleaned

- 50g butter

- Juice of half a lemon

- For the glazed onions:

- 12 shallots or pearl onions blanched and peeled

- 1 tbsp sugar

- 50g butter

- Sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

Instructions

Put the stock, water, carrot, celery, studded onion, bouquet garni and rabbit trimmings in a large pot and bring to a simmer. Cover, and simmer on low for 45 minutes. Once done, and tasting good, Strain the broth through a sieve and discard the solids. Leave the broth uncovered on a low heat to keep warm.

Season the rabbit joints on all sides.

Heat the butter in a large sauté pan until foaming. Cook the rabbit in the butter on a medium heat until just coloured. It will not be cooked through. Remove the meat and set aside.

Add the chopped onion to the pan and cook gently on a medium heat until softened, but not coloured. Add the flour and cook it for 1 minute on low. Take care not to burn it. The butter and flour will form a roux, which is the basis of your velouté.

Start adding broth to the roux a ladle or two at a time, whisking to smooth with each addition. Continue to add and whisk until you have a sauce with coating consistency and just less than half of the stock has been used up. You can keep the remaining stock and freeze it for the next time you make the dish.

Add the cream, mustard and herbs, and stir in. Check your seasoning at this point and adjust as needed. Put the pan on a low bubble and put the rabbit pieces back in to cook. Cooking will take about 50 mins to 1 hour. If you have a probe, you are looking for 75˚C in the thighs.

While the rabbit is cooking, prepare the mushroom and onion garnish. Put the ingredients for the mushrooms in a sauce pan, bring to a boil and then simmer. For the onions, do the same, but add a paper cartouche with a hole in the centre over the surface of the vegetables. Cook the onions until almost all the water has gone.

To serve, place some rabbit pieces on a plate and arrange the garnish around. Spoon over with the mustard sauce. Sprinkle a little tarragon or parsley over the top. Serve with pasta.

Notes

This recipe can be easily adapted to chicken. Just replace every rabbit part with chicken. Pork is another common variant.

(9 votes, average: 3.33 out of 5)

(9 votes, average: 3.33 out of 5)

2 Comments

Rod Lechelt

11/05/2020 at 12:19 amJust came across this site, and its great. I love the history behind the food, without a massive bunch of “Oh My wife/husdand/cvhild/partner like this on a crisp fall day and it reminds me of growing up” or the same old thing from almost every food blog.

Nigel Eastmond

11/05/2020 at 7:02 amThanks Rod. Yes, we hate all that stuff too. For me, understanding a dish is knowing where it came from. Only then do you know how to really make it. And that rabbit in mustard sauce is glorious.