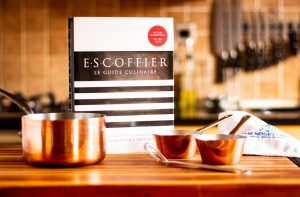

The style of cooking known as salmi is ages old. When Auguste Escoffier described it in his 1903 Le Guide Culinare, even he said it was:

“… bequeathed to us by the old classical kitchen.”

Reading Le Guide Culinaire, and digging around the history of salmis reveals some possible misconceptions. Salmis is prepared by undercooking a roast meat and reheating it in an enriched sauce. Cooking game birds in this manner means that they remain moist from wing to table – game birds can be notoriously dry if not cooked with care. However, some food writers have stated that salmis was originally a means of using up leftover roast game – but that would involve fully cooking the bird before introducing it into the sauce. This technique is lambasted by Escoffier, who writes:

“… its method of preparation has been ruined without discernment by applying it to game already cooked and then reheated …”

This would indicate that the dish was prepared with undercooked meat in the first instance, adapted to leftovers, and then consigned to the compost pile as a recipe of no merit.

The Oxford English Dictionary helps us out a little by stating that the first written reference to ‘salmis’ is in the 1759 book ‘Complete System of Cookery by English innkeeper William Verral. In that book, the recipe for salmis des becasses (woodcock) is absolutely clear that the birds are half roasted. So The Nosey Chef thinks we (and Escoffier) are right when we say that the original method uses part-cooked birds, and that a string of chefs wrecked the dish by stewing off leftovers. This led to it falling into disuse.

Escoffier is careful to point out that if the original method is used then the result is one of the most luxurious and delightful ways to enjoy game. For that reason, we feel the need to get this technique solidly under our belts.

The salmis described here is one for guinea fowl. The original salmis de faisan (pheasant) that Escoffier describes uses an espagnole, stock and meat glaze all made from game. That can be quite tricky to do as you need biblical quantities of game carcasses to do it, so we put in a bit of a cheat and used chicken-based sauces (guinea fowl is a wild chicken, after all). You will need to plan ahead as an espagnole (see our page on mother sauces) takes a long time to make. Glazes can also be a problem until you realise that they are absolutely no different from the stuff inside a Knorr stock pot (i.e. hyper-reduced stock), so just use one of those.

It is worth saying something of Auguste Escoffier’s opinion of guinea fowl. He clearly thinks that they are shit. He devotes one recipe to them, says pheasant is way nicer, and grudgingly accepts that about three of his pheasant dishes could be adapted to the inferior wild chicken. Salmis is one of them.

Salmis de pintade

Ingredients

- For the roast:

- 2 guinea fowl

- 1 lemon, halved

- 50g butter, softened

- 2 cloves of garlic, cracked with the back of a knife

- 2 sprigs of thyme

- For the salmis:

- 2 Knorr chicken stock pots (or game glaze)

- 2 tbsp brandy

- 250ml white wine

- 2 shallots, chopped

- 300ml chicken stock (or game stock)

- 300ml chicken-based espagnole (or game-based)

- 25g butter

- To garnish:

- 12 button mushrooms

- Fresh black truffle, finely sliced (optional)

- Salt and freshly ground black pepper

Instructions

Set an oven to 240˚C.

Smother the birds with the butter, squeeze over the lemon and season liberally. Push the spent lemon halves, garlic and thyme into the cavities. Roast for 10 mins. Decrease the oven temperature to 190˚C and roast for another 10 mins. Remove the birds from the oven, and get them on a chopping board nice and quickly. Joint them into legs, wings and breasts, slicing the jointed breasts lengthways once off the bird. Discard the lemons. Skin the joints with your hands (tricky for the wings, I know) and discard the skin.

Melt the chicken stock pots in a sauté pan. Add the brandy and flame it. Once the flames are out, paint the bird joints with the glaze, cover and keep warm. It is essential that these joints are kept warm, but that the cooking is not advanced by one iota. Either use the absolute lowest setting on your hob or place in an oven at no more than 60˚C.

Heat the wine and shallot in a large pan and season with a little pepper. Break up the bird carcasses and push them down into the wine. Almost completely reduce the wine.

Add the stock and espagnole to the wine and carcasses and cook on medium for 10 minutes. Once done, put the whole lot in a chinois and pass the sauce through the mesh, discarding the solids that won't go through.

Reduce the passed sauce by a third, skimming off any impurities. Stir in the butter.

While the sauce is reducing, quickly cook the mushrooms in a little butter and pepper.

To finish the dish, put the jointed meat in the sauce with the mushrooms (and truffle if using) and cook until the joints are done (about 5–10 mins; use a meat probe to ensure you have 75˚C in the centre of the thighs and take care not to over-do them).

Notes

If preparing one bird or doing a pheasant, then reduce the stock and espagnole quantities by about half.

No Comments